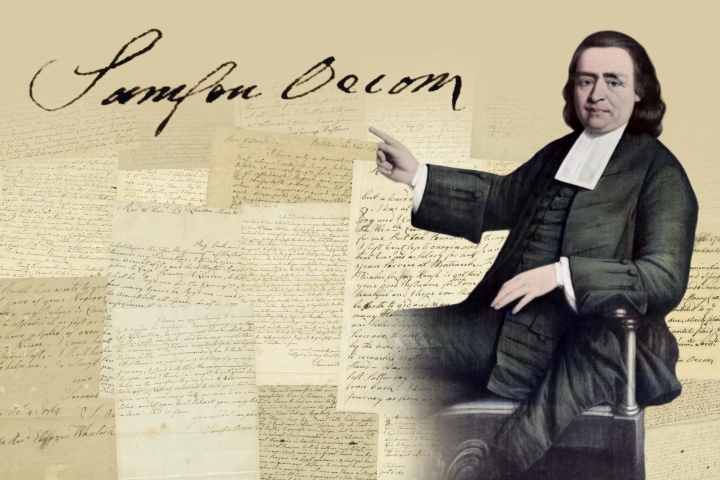

The papers of Samson Occom—the Presbyterian minister, scholar, educator, and member of the Mohegan Tribe who helped Eleazar Wheelock secure the funds for what would become Dartmouth College—are being restored to Occom’s Mohegan homeland, President Philip J. Hanlon ’77 announced today.

President Hanlon will lead a delegation from Dartmouth to Connecticut for an April 27 repatriation ceremony for the papers, which include journals; letters from Occom, Wheelock, and others; traditional plant remedies; some of the earliest known samples of written Mohegan language; and other significant documents.

“The repatriation of the Samson Occom papers to the Mohegan Tribe will serve to renew the historic bonds between the Mohegan Tribe and Dartmouth,” says Bruce Duthu ’80, the Samson Occom Professor of Native American Studies and chair of the Department of Native American and Indigenous Studies. “In returning Occom’s papers to his Mohegan homeland, we acknowledge and celebrate his contributions to the establishment of Dartmouth College and join with the Mohegan Tribe in welcoming their ancestor back home.”

Duthu says it is significant that Dartmouth is returning the Occom papers at a moment when the College is “marking the 50th anniversary of Dartmouth’s recommitment to its founding purpose, including the establishment of an academic program—now department—in Native American studies. This was the very purpose to which Occom dedicated years of service to help achieve.”

Sarah Harris ’00, vice chairwoman of the Mohegan Tribal Council and a member of Dartmouth’s Native American Visiting Committee, which advises the president on Native American issues, says the repatriation holds special meaning for the Tribe.

“The Mohegan People believe that every object or writing holds within it the spirit of its maker,” Harris says. “With the return of his papers, Occom is coming back to our homelands and our people. This repatriation is particularly meaningful because Occom felt betrayed by Wheelock. Due in part to his crushing disappointment with Wheelock’s diversion from the planned school for Native students, Occom left Mohegan and New England altogether. This repatriation marks the beginning of a new chapter in the shared history of the Mohegan People and the Dartmouth community, one in which Occom’s dream of an education for Native students moves closer to fulfillment.”

The ceremony, which is for members of the tribal community and invited guests, will take place outdoors at the Mohegan Church in Uncasville, Conn., on land that has belonged to the Mohegan people since before Europeans arrived in North America. Afterward, attendees will view the Mohegan cultural center where the papers will be housed.

“In this year when Dartmouth is celebrating the anniversary of the College’s rededication to the education of Native American students, it is meaningful and appropriate to mark this occasion with the transfer of the Occom papers to the Mohegan Tribe,” Hanlon says.

Dartmouth uses the Occom papers in its teaching and has digitized copies of the materials that will be given to the Mohegan.

A Complicated History

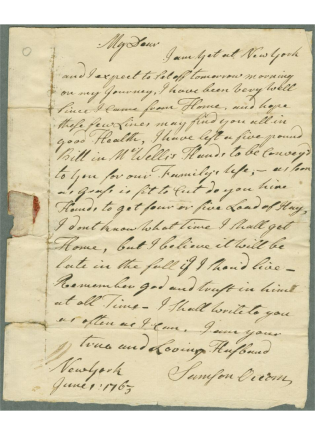

Born in 1723 on Mohegan land near New London, Conn., Occom was one of the first ordained Native American Christian ministers. In 1766, when Occom traveled to England to raise money for Wheelock’s new school, he believed Wheelock intended the funds to support Indigenous students.

His journey was a wild success, in part because Occom himself was an embodiment of the kind of Christian education Wheelock’s school promised to Native students, says College Archivist Peter Carini. The more than £9,494 in donations that Occom secured provided a critical foundation for what would become Dartmouth College.

“It would have been hard for the College to start without that money,” Carini says.

But while Dartmouth’s charter of 1769 details its mission “for the education and instruction of youth of the Indian tribes in this land,” by the time Occom returned from his fundraising mission, Wheelock had already shifted the school’s direction toward the sons of white New England families, and moved the school from Connecticut to New Hampshire. Between 1769 and 1970, Dartmouth graduated only 20 Native students.

“Your having so many white scholars and so few or no Indian scholars, gives me great discouragement,” Occom wrote to Wheelock in a July 1771 letter included in the collection. “I was quite willing to become a gazing stock, yea even a laughing stock, in strange countries to promote your cause. … But when we got home behold all the glory had decayed and now I am afraid, we shall be deem’d as liars and deceivers in Europe, unless you gather Indians quickly to your College, in great numbers.”

After this disappointment, Occom continued to be an outspoken advocate for Indian rights. When the colonial government of Connecticut refused to compensate Mohegans for their land, he helped found a community from various tribes in Oneida country in upstate New York. And his legacy as a Christian religious leader helped the Mohegan community that remained in Connecticut withstand later efforts to relocate them, according to the Mohegan Tribe website. Occom died in 1792.

‘An Incredible Group of Materials’

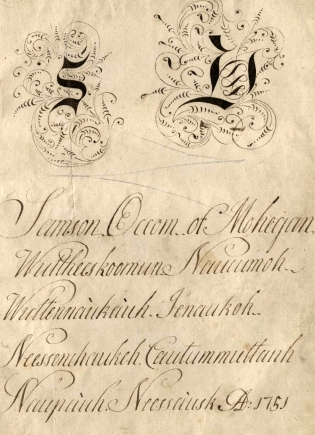

In addition to letters and journals, the collection includes “a Hebrew primer that was probably the first book Occom acquired,” says Carini. “Occom writes throughout the book, ‘Samson Occom, Mohegan Indian, his book,’ in five languages—Greek, Latin, English, Mohegan, and Hebrew. It’s a very significant document because it shows his language abilities and scholarship, and also he’s written out Mohegan language, probably for the first time that that’s ever been done.”

It also includes an herbal—a handwritten record of the medicinal uses of various plants. Carini notes that at the time, Mohegan herb lore was traditionally women’s knowledge. “The fact that Occom knew and was recording that knowledge may indicate that he understood its fragility—perhaps he was trying to record it in a way that would be accessible in the future, if the line was broken.”

“It’s an incredible group of materials,” Carini says of the collection. “And they’re going to their rightful home, the place where they’ll be within the context of the land and the people whom Occom was championing, and that’s really good.”

Carini recently visited the Mohegan cultural center where the papers will live and says that the collection will be in good hands. “They have very good facilities—equal to or better than where we store them now, and they are planning renovations that would allow for outside researchers to use the archives.”

Ongoing Partnerships

The process of selecting which materials will return to the Mohegan has involved a team effort on campus, taking advantage of the infrastructure of a recent Mellon Foundation grant to advance significant cross-institutional and community-centered collaboration grounded in Dartmouth’s Native American and Indigenous Arctic collections, Carini says.

Dartmouth and the Mohegan archives use the same collection management system, which will allow Dartmouth to share cataloging information and metadata “so that when scholars come looking for documents here, we can redirect them to Mohegan,” he says.

While the Occom papers will no longer physically live in Dartmouth Library’s Rauner Special Collections Library, members of the Dartmouth community and the general public will still be able to access them digitally through the Occom Circle project led by Professor of English and Creative Writing Ivy Schweitzer, which was funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Neukom Institute for Computational Science, and the Dartmouth Center for the Advancement of Learning.

“Part of the agreement with Mohegan is that we can keep the digital versions and the transcriptions up,” Carini says. “So we aren’t losing the context of those documents from the documents around them in the Wheelock collection or other parts of our collections. We may be losing the original, but we’re gaining the ability to share with students and others the importance of returning these documents to a place with a different kind of context.”

“While important historical documents related to Dartmouth will no longer be part of our physical collections, it is important that institutions be open to the concept of the repatriation of archival documents and materials that hold a different importance for Indigenous communities,” says Dean of Libraries Sue Mehrer. “My hope is that this will be the beginning of a long collaboration between Dartmouth and Mohegan that will lead to further connections and collaborations.”

The Native American Visiting Committee has advocated for Dartmouth to better recognize Occom’s contributions to its founding, and his disagreements with Wheelock, says Harris, the Mohegan Tribal Council vice chairwoman. It was the committee that brought the repatriation idea to Hanlon.

“As the members of the NAVC discussed the 50th anniversary of Dartmouth’s revival of its founding commitment to educate Native American students, we felt it was important for the College to more meaningfully acknowledge the truth of its founding,” she says. “It’s important for Native students to understand that they were foundational to the institution and for the broader community to understand our shared past, including some of the more difficult or painful aspects of it.”

The return of Occom’s papers is part of this effort, she says. “The repatriation of Occom’s papers shows Dartmouth’s level of commitment to honoring our ancestor and moving forward in a good way. The Tribe is grateful to President Hanlon, as well as Sue Mehrer, Peter Carini, and their staff for all they have done to make this homecoming possible. We hope that this reconciliation and repatriation paves the way for close collaboration between the Tribe and Dartmouth moving forward and inspires other institutions to follow Dartmouth’s lead.”

Carini recalls being present when committee members were told Dartmouth would restore Occom’s papers to his homeland.

“One of most touching moments in my entire career was watching the reaction of the Native American Visiting Committee to the announcement that we were going to repatriate these papers,” Carini says. “People teared up. It was very emotional—one of those few moments when you work as a professional where you have a feeling like, ‘I’ve just witnessed a stunning historical moment.’ ”